Too Little, Too Late

"At this juncture, the belated decision by the regime to grant access to the U.N. team is too late to be credible, including because the evidence available has been significantly corrupted as a result of the regime's persistent shelling and other intentional actions over the last five days." WSJ

Right Decision

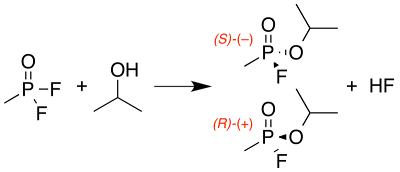

Nerve agents are predominately organophosphates which degrade rapidly upon exposure to sunlight, air, and soil. So rapidly in fact that during the time I was in the military I witnessed the transition of response from OMG CHEMICAL WEAPONS... in which upon warning of attack everyone went to MOPP-4 (Mission Oriented Protective Posture, MOPP-4 being full suit, gloves, boots and mask) and stayed, there to the concept of split-MOPP levels.Fact is, depending on the agent and environmental conditions the hazard can be significantly reduced in as little as 30-90 minutes. Weapons such as Sarin, which is alleged to have been used in the apparent chemical attack in Syria rapidly dissipates about 30 minutes after exposure and testing for Sarin after a week is considered unviable.

The Point is...

Syria's offer to allow UN inspectors in a week after the attack is meaningless. They know full well that after all this time the inspectors will be unable to find anything. French testing of physiological samples (blood, urine, tissue) have confirmed the use of Sarin. Even before the latest attack (4 June), the French have confirmed the use of Sarin in Syria. The only question now is who used it?It is highly doubtful that the rebels are manufacturing military grade nerve agents, although they could have obtained it by capture or from an outside agency. It is also highly unlikely they are using it against themselves in an effort to discredit the regime, although that would seem to be a remote possibility one must consider.

Many use the argument that Assad would have to be crazy (although that has yet to be determined) to use chemical weapons upon the arrival of a UN chemical weapons inspection team. But the fact that the team is there is largely irrelevant, they are unable to test or corroborate the usage while under the control of the Syrian government despite being only a short drive from the location of the attacks. The risk present to Assad is no greater with the team present than without. So that leaves the general hazard of an international response, a response from a community that has so far done nothing in way of response to prior use.

A More Important Question

Dominic Tierney asks a good question in The AtlanticWhy is 1300 dead by chemical weapons a red line when 100,000 dead via conventional means is not? Or better yet, millions in the Congo not? While I am not attempting to legitimize the use of chemical weapons... dead is dead. Whether it is by Sarin or Semtex, it wouldn't seem to be of much relevance to the deceased. Is the suffering from Sarin worse than the suffering of getting your limbs blown off and bleeding out? Chemical agents are silent, deadly, and thus scary... but is there a moral or ethical difference between killing 1300 with Sarin and 1300 with high explosives?

I am not advocating for or against intervention in Syria, I'll leave you to make up your own minds about that. What this is, is an attempt to elicit thought and discussion on the circumstances and use of chemical weapons and the motivation behind intervention.

No comments:

Post a Comment